.

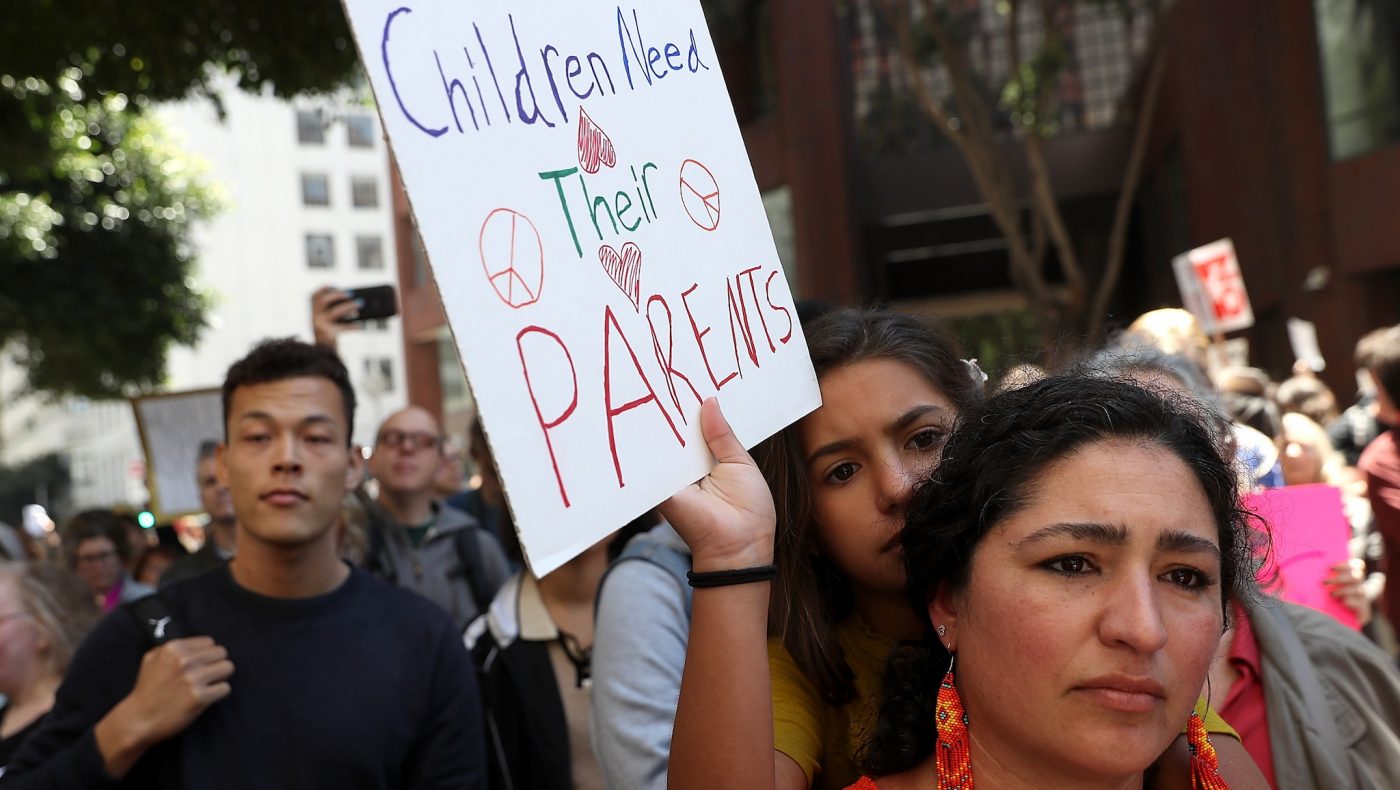

A young girl holds a sign during a demonstration outside of the San Francisco

office of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). |

|

Psychological Damage Inflicted By Parent-Child Separation is Deep, Long-Lasting

by Allison Eck -- NOVA / PBS SoCal

Millions of years of evolution have gone into erecting the deepest of connections: that between mother and child.

That primal bond—when forcibly shattered or disrupted—can be devastating for both parent and child, according to scientists, many of whom are weighing in on the White House's recent “zero-tolerance” policy designed to crack down on undocumented immigrants.

“Based on empirical evidence of the psychological harm that children and parents experience when separated,” wrote experts from the American Psychological Association in a letter to President Trump, “we implore you to reconsider this policy and commit to the more humane practice of housing families together pending immigration proceedings to protect them from further trauma.” |

Many other organizations, including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, have released similar statements.

On May 7, U.S. attorney general Jeff Sessions announced that the Department of Homeland Security would refer 100% of illegal immigrants crossing the border for criminal prosecution in federal court. Any minors accompanying them were to be taken into government custody.

In the past, immigrants charged with this misdemeanor were able to stay in shelters with their children while waiting for further direction.

The story is moving quickly. President Trump declared today that he plans to issue an executive order to end the separation of families at the border by indefinitely detaining parents and children together.

Still, in a six-week period, nearly 2,000 children—some as young as 18 months old—were separated from their caregivers. Yesterday, the Associated Press reported that babies and other young members of this group are living in “tender age” shelters in South Texas.

“I would definitely consider [this] a traumatic experience with long-term consequences,” said Chandra Ghosh Ippen, associate director and dissemination director of the Child Trauma Research Program at the University of California, San Francisco and the Earth Trauma Treatment Network.

When a child is separated from his or her parents under chaotic circumstances, a monsoon of stress hormones (like cortisol) floods the brain and the body. These hormones are important for navigating stress in the short-term. However, in high doses, these chemicals—if hyperactive for a prolonged period of time—can increase the risk of lasting, destructive complications like heart disease, diabetes, and even some forms of cancer. In addition, multiples instances of trauma early in life can lead to mental health problems like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

On top of this immediate biological response to separation is the frightening experience of watching a caregiver undergo severe emotional upheaval.

“When a child sees a parent frightened, it is extremely threatening,” said Lisa Berlin, an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Social Work and co-author on a study published in 2011 examining the effects of mother-child separation on children under two years old. Regarding that study, Berlin notes that some of the participants experienced planned separations that were done “in an orderly way.” By contrast, she says, “this is chaos.”

The conditions under which these undocumented minors are now living are varied and unclear, but ProPublica obtained audio suggesting that the children are under duress.

“It sounds like, from what we're hearing, that there aren't people there to help console them and help them self-soothe, which would be something that would be really key to help offset those biological responses [to stress],” said Erin C. Dunn, a social and psychiatric epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital's Center for Genomic Medicine.

The situation is a case study in what psychologists call “attachment,” and it's the reason why children who are separated from their primary caregivers desperately need replacement care.

“In early childhood, young children believe that their parents can protect them from anything, and that's actually what allows them to feel safe enough to explore the world,” Ippen said. “When that safe base is disrupted, you might see a child who is very anxious, or who is clingy, or you might see a child who goes off and recklessly explores the world. This is the crux of attachment theory.”

Attachment theory is a set of ideas developed in the early 1950s by British psychiatrist John Bowlby. “It's an explanation of why we are the way we are,” Berlin said. “[Bowlby] said that a big determining factor has to do with how much we can rely on our primary caregiver when we really, really need them. We need them for physical safety and because we're young and immature and we can't make sense of our world without their help.”

Berlin says that many rigorous research projects since Bowlby's original writings have demonstrated that these ideas make sense; in other words, empirical evidence has confirmed his theory, as well as how a child's future development is based on these patterns formed early on.

“Even when children are in the care of parents who may not be able to meet their needs or to keep them safe, they still organize their behaviors and thinking around these relationships and go at great lengths to maintain them,” said Carmen Rosa Noroña, Child Trauma Clinical Services and Training Lead of Boston Medical Center's Child Witness to Violence Project. Moreover, when these attachment relationships are suddenly subverted and there is no other adult who can help the child make meaning—or a story—of what has happened, the child might experience not only a sense of confusion and terror but might also blame himself or herself for losing the parent.

“All they know is that the people who were there to protect them and help with every little thing are no longer there,” Berlin said.

Parents, of course, face similar trauma. Especially in Latin America, the concept of motherhood is heavily linked to the idea of the self-sacrificing woman. “[That identity] permeates across the countries in Latin America,” said Gabrielle Oliveira, an assistant professor at the Lynch School of Education at Boston College and an expert on the concept of “transnational motherhood,” or the notion that women can engage in the care of their children across borders. Oliveira says that women who decide to migrate with their children to a new country usually view it as a safer option for the whole family than staying put.

“If the very beneficiary of that crossing gets taken from them, it defeats the entire purpose,” Oliveira said. Yet another layer of guilt gets added to the equation. “That is so beyond traumatic.”

Dunn says that what has happened is especially scary because evidence suggests that the effects of stress and trauma vary based on the age of the child—the youngest children may be the most vulnerable.

“The scientific evidence against separating children from families is crystal clear,” she said. “No one in the scientific community would dispute it—it's not like other topics where there is more debate among scientists. We all know it is bad for children to be separated from caregivers. Given the scientific evidence, it is malicious and amounts to child abuse.”

Noroña agrees.

“It's a form of systemic violence, and it's becoming normalized,” she said.

This article was edited on June 21, 2018, for clarity.

|